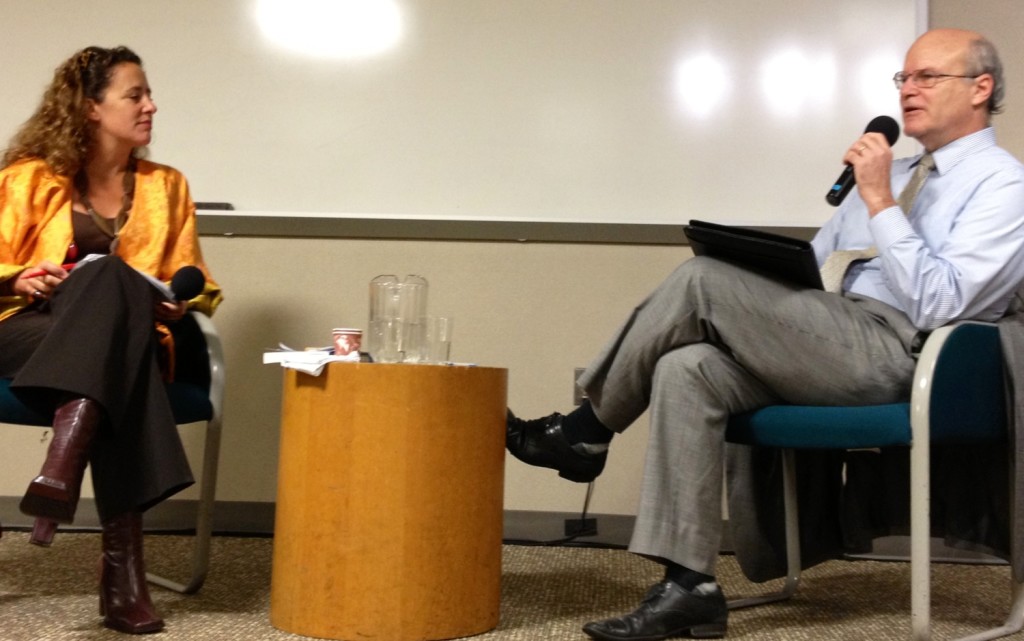

By Donald Steinberg, President of World Learning

Don Steinberg was the special guest speaker at October’s Conflict Prevention & Resolution Forum in Washington DC, moderated by Sandra Melone of Search. He is the former Deputy Administrator at USAID and a former Ambassador to Angola.

“The U.S. will join with our allies to eradicate extreme poverty in the next two decades: by connecting more people to the global economy; by empowering women; by giving our young and brightest minds new opportunities to serve; by helping communities to feed, power, and educate themselves; by saving the world’s children from preventable deaths; and by realizing the promise of an AIDS-free generation.” ~President Obama’s State of the Union address:

These words are inspirational, but they are not a pipe-dream. Working together, we have brought 600 million people across the poverty line in the last decade and a half. We have reduced infant and maternal mortality by a third. More students, especially girls, are getting quality educations in school than ever before. Reportedly, Google has set aside money to build a poverty museum, because the expectation is that by 2035, the only place you could see extreme poverty will be in a museum.

But we cannot achieve these objectives without peace and rule of law. Armed conflict is a development destroyer. Literally decades of painstaking efforts to build good governance, ensure physical security, and address the challenges of human security in health, education, housing, nutrition, can be wiped out within weeks as soon as the guns start blazing. It is reported that not a single Millennium Development Goal has been met in a fragile and conflict state.

There are natural linkages between development and stability, and no place demonstrates that linkage better than Afghanistan. The far-from-perfect peace in Afghanistan has permitted momentous improvements in socio-economic and humanitarian conditions. Afghanistan has achieved one of the fastest growth rates in the world since the Taliban’s fall. Infant and maternal mortality rates have plummeted by nearly two-thirds, along with similar achievements in other health and socio-economic indicators. As a result, life expectancy has increased by 15 to 20 years in little more than a decade – from 47 years when the Taliban was in control to 62 years or more today.

For women and girls, the changes are even more remarkable. Today, three million Afghan girls are in school, in contrast to none when the Taliban ruled. Last year, some 120,000 girls graduated from high school; 40,000 young women are in university; and the percentage of women in the Afghan parliament (25 percent) is greater than in the U.S. Congress.

The question is whether these achievements will be matched by progress in the political and security arenas, and whether they can survive the withdrawal of international combat forces. Will the achievements of women in particular be sacrificed on the altar of a false peace with the Taliban? Part of the answer to that question depends on whether they are going to have international support for their transition. It will be harder for spoilers to win the hearts and minds of the Afghan people if there is a continuing “peace dividend.”

By contrast, the landscape is less promising in other regions. In the Sahel, resource conflicts, poverty, international migration, climate change, extremism and governance deficits come together in a witches’ brew that threatens not only those countries, but countries and people around the world. In Central America and Central Africa alike, the end of formal conflict in recent years has led to an even more pernicious pattern of death and suffering from criminal violence, domestic violence, and sexual violence — the key word here is “violence” — that has killed more people than the war itself.

There is a growing international recognition of the connection between development and stable and just states. The New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States established a very clear link between development and conflict. This is a promising development. Two years ago, I led the U.S. government delegation to a U.N. conference in Istanbul on the least developed countries. Based on pre-conference consultations, I wasn’t allowed to even mention the word “fragility” as a factor in continuing poverty in least developed countries. Now, dozens of countries are self-identifying as “fragile,” and calling for special treatment as a result.

What does this mean for our efforts? If we are going to respond to conflict through development, or more importantly, if we are going to seek to forestall or defuse conflict around the world, we need to know where to focus. So where and how does conflict originate?

Seven Deadly Synergies

At the risk of over-simplification, I want to draw from my own background and the research done at World Learning. I can summarize my own experience and research into seven factors which, when they come together, can build more dangerous tensions than the sum of their parts. I call these the “Seven Deadly Synergies.”

- Rapid urbanization and population pressure coupled with weak economies. One of the quickest routes to conflict is when the potential demographic dividend from a large youth population gets transformed into dangerous youth bulge. Young people who do not see opportunities for positive contributions within their societies, are more susceptible to fanatics and zealots.

- Lack of political participation, responsive governance, and rule of law. Societies must have safety valves to permit the peaceful redress of grievances.

- The absence of institutions of civil society that draw populations together across potentially divisive religious, ethnic, class, regional, and political lines. Having multiple identities such as journalists, women, academics, lawyers, etc., tends to emphasize the centripetal forces at play in societies

- “Location, location, location,” the role of neighbors in either mediating or fueling disputes is fundamental. Countries in bad neighborhoods risk spill-over from armed combatants, refugees and arms flows; those in good neighborhoods receive a powerful dampening effect on political and potential violence.

- The degree to which the society is militarized or, put another way, whether there has been a “normalization of violence.” Are human interactions carried out and normal conflict resolved in the presence of a gun? Factors at play here include the role of military and security forces in political structures and the proliferation of small arms and light weapons.

- The extent to which the society is closed, especially to international influences. Closed political systems, economies, and media environment are dangerous. Conflicts are like mushrooms: they grow best in darkness.

- The final factor is something you hear about in investment perspectives. Except that in this case, past record is an indicator of future performance. The single most reliable determinant as to whether conflict is going to emerge in a society is whether there has been conflict in the last 10 to 15 years.

So, if these seven factors are the ones we are focused on, what does this mean for our efforts?

Interlocking Challenges for Successful Peace Building

Throughout the conflict prevention and peace building community, we have all studied dozens of successful and failed peacekeeping and peace building efforts since World War II. We have found that five key challenges must be addressed nearly simultaneously in order to build peace and justice. These are restoring security and stability, building a political framework, kick-starting the economy, establishing a sense of justice and accountability for past abuses, and promoting civil society.

Security: In post-conflict societies, the international community tends to rely on the security blanket of international peacekeepers. Indeed, the 100,000 or so U.N. peacekeepers and lesser numbers of other regional peacekeepers can provide a buffer. But, as soon as possible credible local security forces must take over to provide a sense of stability, normalcy and rule of law to everyday life. International support for security sector reform is key to ensuring that forces are well-trained, disciplined, and adequately paid so that they do not exploit and abuse the populations they are supposed to protect.

There must be effective programs for disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration, and we need in particular to address the tragic phenomenon of child soldiers. Children must be permitted to put down their AK-47s and pick up schoolbooks.

Governance: The second challenge is to restore legitimate political frameworks. Confidence in government must exist at national and local levels; armed movements must be transformed into political parties; and effective legislatures and judiciaries must be restored to counter-balance the power of the executive. A culture of accountability is necessary along with an effective system to protect human rights. Decentralization and empowerment of provincial and local institutions is essential but it also has to be balanced against the need for central authorities to take tough steps to rein in regional warlords and other recidivist actors.

Development: Third is the question of economic renewal. We can define this in two ways. First is the physical reconstruction of damage from the conflict: the rebuilding of roads, clinics, schools, power grids, and houses. At the same time, the challenge of reviving agriculture, creating conditions needed to attract local and foreign investment, and ensuring job creation must be addressed in order to build popular support for the benefits of peace. Again, it is no surprise that in countries that have 90 percent youth unemployment, renegade leaders like Foday Sankoh in Sierra Leone, Joseph Kony in Uganda, and Jonas Savimbi in Angola could lure or kidnap disaffected youth with a siren song that offers quick, if venal, empowerment and meaning to their lives.

Growth must be inclusive. It is not enough to ensure high economic growth rates. Given the depressed state of the economy in most countries coming out of conflict, high growth rates are relatively easy to achieve. But growth has to be evenly distributed; it has to create jobs; it has to be free from corruption; and it has to result in improved housing, health care and education. Countries affected by the Arab Spring achieved rapid growth rates of up to ten percent. But jobs were not created. Economic benefits were badly distributed, subject to corruption and did not create socio-economic advancements. The result was a social revolution – a revolution that I believe was absolutely necessary but one that comes at great cost.

Transitional Justice: The fourth challenge is coming to grips with past abuses and atrocities. Nations and individuals who have suffered grievous treatment must balance immediate accountability and long-term national reconciliation. Too frequently the urge is to try and forget the past, but that generally doesn’t work. Transitional justice addressed through generous amnesties means that men with guns forgive other men with guns for crimes committed against women and children in the conflict.

There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to transitional justice. Whether it is action by local courts, the International Criminal Court, a truth and reconciliation commission, the gacaca community court system in Rwanda, or ad hoc international tribunals where local courts are inadequate, ensuring accountability is essential to rebuilding the concept of rule of law and eliminating a culture of impunity.

Civil Society: The final challenge, one that is often ignored, is the re-building of civil society. Groups like Search for Common Ground and World Learning are working to develop institutions of academics and lawyers and journalists and women. This is the glue that holds society together. Put another way, it provides the safety valves that permit the peaceful redress of grievances. Such groups are frequently polarized and/or marginalized during conflict, often as a conscious effort by governments or rebels to “divide-and-rule”. Disadvantaged minorities, including IDPs and refugees, along with women, people with disabilities, the LGBT, and indigenous populations must be drawn into the mix.

Women, Peace and Security

Women are not only the primary victims of conflict, but a key to peace. I have found, throughout my career in negotiating and implementing peace agreements in half a dozen countries that, bringing women to peace tables improves the quality of the agreements reached. Involving women in post-conflict governance reduces the likelihood of a return to war.

The single best investment — to revitalize agriculture, restore health systems, and improve other social indicators after conflicts — is girls’ education. It has been said: “Educate a boy and you educate an individual; educate a girl and you educate a community.”

These issues — restoring security, building a political framework, kick-starting the economy, ensuring justice and accountability, and promoting civil society — used to be considered the “soft side” of peacebuilding. We used to draw this hard line between the physical security dimension and the human security dimension. I believe that this line has been blurred.

There is nothing soft about stopping traffickers who turn young people into commodities. There is nothing soft about preventing armed thugs from abusing people in refugee camps, or holding warlords accountable for actions against civilians, or insisting that girls’ health, education, and safety are addressed in peace negotiations and post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation.

These are among the hardest challenges we face in international peacebuilding and international development.

By Gabrielle Solanet

Last weekend, Searchers and their partners across the world celebrated International Peace Day. In the Great Lakes of Africa, our local teams used fun activities to mobilize the masses and spread key messages of peace that transcended borders.

The Great Lakes have suffered from profound violence, particularly since the M23 insurgency took control of key areas in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in 2012, reviving diplomatic tensions between the DRC and its neighbor, Rwanda, and causing the death and displacement of thousands of Congolese civilians. Against this backdrop, Search engaged local citizens into a series of activities aimed at promoting peace and social cohesion in communities across the region.

In the DRC:

The Search North Kivu team organized a peace marathon across the city of Goma, conveying hope and peace to the population. Four hundred runners supported the cause. Marathoners held banners that read “Respect, Tolerance and Justice – My Combat for Peace”. Goma’s population cheered for them all along their route. Following the race, 3,000 community members attended peace concerts. Popular Congolese artists entertained the crowd, unified under the message: “I personally commit to peace, what about you?”

Parallel to the concerts, Search organized a “Seat Ball” Paralympics match where people with physical disabilities from Goma and Gisenyi (in neighboring Rwanda) competed against each other. Altogether, the marathon, concerts and Paralympics created social cohesion amongst divided populations.

Parallel to the concerts, Search organized a “Seat Ball” Paralympics match where people with physical disabilities from Goma and Gisenyi (in neighboring Rwanda) competed against each other. Altogether, the marathon, concerts and Paralympics created social cohesion amongst divided populations.

“Today is the most beautiful day of my life in the past 20 years,” Jean-Robert N’Senga, Coordinator of CIVIS CONGO, a local civic rights association.

The Kivu team also brought several international and local NGOs together to celebrate in the festivities, including Goma’s Youth Cultural Center, the Youth Movement for Change, International Alert, the United Nations’ Refugee Agency and many others.

“Today’s initiatives demonstrated the victory of courage over fear and of unity over exclusion. Peace is a long and challenging process, but it is by taking steps forward, like today, that this dream of peace will one day become a reality,”Vianney Bisimwa, Peace & Reconciliation Officer at SFCG-Goma.

Meanwhile, in South Kivu Search organized a public radio and TV debate, revealing how people can positively bring peace to the DRC and support its democratic institutions. The debate triggered an open dialogue between university students, military and police officers, Congolese civil society organizations, representatives from the Governorate of South Kivu, and the UN Mission to the DR Congo. It will broadcast on the Congolese

Meanwhile, in South Kivu Search organized a public radio and TV debate, revealing how people can positively bring peace to the DRC and support its democratic institutions. The debate triggered an open dialogue between university students, military and police officers, Congolese civil society organizations, representatives from the Governorate of South Kivu, and the UN Mission to the DR Congo. It will broadcast on the Congolese

National Radio Television Channel, the North and South Kivu Radio Television Channel, and TV Vision SHALA throughout the entire month of October 2013.

In Burundi:

Search mobilized 700 Burundian youth across dividing lines in a big march for peace across the capital, Bujumbura. The march  engaged youth from scouts’ movements, civil society, political parties’ youth wings, and representatives from the Burundian Ministry of Youth. The march passed through symbolic places in Bujumbura’s city center, finishing at the scouts’ headquarters. There the youth participated in peace-themed games, poems, and theater competitions. The activity received vast media coverage from national TV and radio stations, bringing together media from different editorial lines to cover the event.

engaged youth from scouts’ movements, civil society, political parties’ youth wings, and representatives from the Burundian Ministry of Youth. The march passed through symbolic places in Bujumbura’s city center, finishing at the scouts’ headquarters. There the youth participated in peace-themed games, poems, and theater competitions. The activity received vast media coverage from national TV and radio stations, bringing together media from different editorial lines to cover the event.

In Rwanda:

Search in Rwanda produced three radio spots for peace. The first spot asked Rwandan celebrities (musicians, actors, and religious leaders) the question: “What does peace mean to you?” The second spot asked ordinary people to describe “what other people do for you to favor peace.” While the third spot focused on peaceful collaboration with the core message: “one’s neighbor is also a brother.” The three spots are currently being broadcast on four community radio stations and two national radio stations. In addition to the radio spots, SFCG: Rwanda also supported peace efforts led by the Rwandan government’s National Unity and Reconciliation Commission to celebrate International Peace Day by providing t-shirts to the participants in the different activities organized across Kigali’s universities.

At the regional level:

Search’s regional live youth radio program Generation Great Lakes dedicated its Saturday show to International Peace Day. Journalists based in DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi covered all of these peace events live, and they aired simultaneously on our partner radio stations across the three countries. Youth from the region heard how their peers across the border mobilized for peace, shared the obstacles that they encountered, identified together possible solutions towards regional peace, and defined the role of youth in this process.

“Congolese, Rwandan and Burundian populations should look first at what unifies them, not what divides them,” GGL listener from Kigali, Rwanda

______________________

Gabrielle Solanet is a Regional Project Coordinator with Search for Common Ground. Based out of Brussels, she coordinates two regional projects in the Great Lakes’ region of Africa and one project in Ethiopia

By Wassy Kambale

“I really liked this story. I read the whole comic book and I learned that it is important to stay united to better develop,” says Messo. This father of eleven children is the Chief of the village Kalawa Messo.

By the Congo River, in a village in Katanga in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, this traditional leader shares with me what he learned from the comic book distributed by Search.

It tells the story of Nsimire, a woman who convinces her husband Mushaga to allow their daughter Mado to go to school instead of being given away in an early marriage. Mado and Nsimire then go on to play major roles in the development of the village.

Messo Kene Kene recieved the “Mopila” comic book thanks to a team of the Tuungane Program, a program implemented by IRC, Search’s partner that seeks to strengthen good governance by working with local populations. This comic book was conceived as a tool to raise awareness for the program.

To reach this village, I had to walk along a long dusty path, cross a few rivers, go down a ravine and back up a hill. Only ten hay houses sit parallel to a line of mango trees.

Some children are playing with a ball made of used plastic bags. Three women are sitting on the floor braiding mats. Further away, in a little church with no roof, we can see a few young people beating pieces of wood on a thick tree trunk, while singing local songs.

The village chief got off his old bicycle to take me to his house, a hay house just a little bit bigger than the other ones. I try to wipe a few drops of sweat from my forehead, the result of a long walk under the beating sun. “I really admire the Centre Lokolé,” (the name of Search in DRC which more easily pronounced here than Search for Common Ground). Within a few minutes, the old wise men of the village surround me with their curious looks as I introduce myself: “I work for the Centre Lokolé, in the Tuungane program.”

Visibly, everyone has heard of the Centre Lokolé and of the Tuungane program. Later, I learn from Chief Messo that this is the result of the distribution of comic books in the village, as well as, the broadcast of shows on two local radio stations that are situated ten kilometers away. Search supports those two community radio stations in the territory of Kongolo and encourages them to produce shows on good governance. These shows are followed in villages in the area, including the village of Kalawa Messo.

This village is particularly known for its mysterious hills called the “doors of hell”. In legends, these are stone hills are the temple of the most powerful god of the region, god Nyange. “Our god is very powerful. There are people who came here and obtained great responsibilities in the country,” proudly explains chief Messo. He is the one who holds the secret. According to the village legend, no one can meet god Nyange without first seeing chief Messo.

Despite his absolute and almost divine power, Chief Messo says he changed his perception of women thanks to the Tuungane program. “We learned to give a voice to women. Now they are included in the village development committee, where the big decisions are taken, like the rehabilitation of roads, or the construction of the village school,” says Messo, before leading me on a free tour of the “doors of hell”.

I walk along another dusty path with him and two other village youngsters. A light wind blows and sometimes lifts a few leaves from the ground. The sun is nearing the horizon to remind us that it is nearly the end of the day. Twenty minutes later, the noise of the Congo River waters reach my ears and chief Messo tells me that we have nearly reached our destination and that I should not forget to support his villagers.

For him, the comic book educates and should be available to the populations of even the most unreachable villages. “I would have like that the people of my village receive every publication of the Mopila comic book series. Everyone loves those comic books here.”

In front of me lay the Congo waters that prevent me from reaching this god, an imposing stone island that splits the waters of the river in front of me.

I take a moment and proudly consider what we achieve through our work here, and the changes I see right before my eyes.

To learn more about our comic books in the DRC, click here.

______________________________

Wassy Kambale is native-born Congolese. He is currently the Tuungane Program Assistant for Search for Common Ground: Democratic Republic of Congo.

By The SFCG Lebanon Team

What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when video games such as Call of Duty, Bullet Storm and MadWorld are mentioned? Most people would probably say violence, guns and conflict.

Search is looking to change all of that.

At Search, we are always looking for innovative ways to promote conflict transformation and peacebuilding. We know from experience that popular culture is a powerful way of conveying messages such as acceptance of the “other” and tolerance without causing people to lose interest.

Our aim with our new video game, Cedaria: Blackout, is to provide the youth in the Middle East a platform to learn and practice how to mediate conflict, solve community problems collaboratively, and understand the perspectives of the “other”.

At a time of escalating violence in the region, we believe that gaming is an effective and innovative tool to reach out to young people and promote non-violent behavior without being boring or patronizing.

This idea is supported by studies showing that skills learned while playing video games are transferable to real life situations. If in a virtual world players can explore options that go beyond socially accepted norms, they will be more inclined to replicate similar behaviors in their everyday life.

Lebanon and the Middle East

Living in the Middle East, one can’t help but wonder why there aren’t more initiatives similar to this one. People of all ages own smartphones and use them to play video games. A colleague once mentioned that during the civil war, he and his cousins were spending time playing video games and this became their most lasting memory from that period of their life. That’s when we knew we had to turn our idea into reality!

With traditional peacebuilding activities we tend to focus on the same target group, but a video game would allow us to reach a new audience. In the pre-production process, we

conducted a survey that highlighted how Lebanese youth spend several hours every day playing video games, reinforcing the notion that video games can be effective in youths’ daily lives. Video games also allow people from different backgrounds and sectarian groups to interact.

As a peacebuilding organization our expertise in creating a video game was limited. In order to make sure we could develop a truly entertaining video game, we teamed up with highly innovative game developers. Some of them had worked on violent games such as Assassin’s Creed and Far Cry, but found our project a breath of fresh air.

So what does it look like?

We wanted to ensure that the game was both educational and entertaining. We did so by combining:

We wanted to ensure that the game was both educational and entertaining. We did so by combining:

- Dialogue designed with the constant feedback of our very own conflict resolution specialists to ensure we teach youth the necessary skills through experience and practice

- Game scenarios giving players the freedom to choose between cooperative and non-cooperative behavior in which they experience the consequences of their choices.

- Steampunk style that gives the characters an edgy look and allows us to explore certain dynamics that are characteristic of the Middle East without breaking the “suspension of disbelief.”

- Middle Eastern elements so that the players can identify with the game setting.

How to help us!

Search received funding from the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Beirut to develop the video game. However, in order to complete the game in line with the original vision we need additional funding. To this end we launched a crowd funding campaign on Kickstarter.

If you want to help us with this INNOVATIVE project in the Middle East you can do so by:

1. Donating to our project. It’s really simple:

- Go to Kickstarter.

- Click on “BACK THIS PROJECT” and register your profile.

- Choose the amount of your donation.

2. Helping us spread the word!

- Like our Facebook page and share it with your friends.

- Follow us on Twitter and tweet us to your followers.

- Watch us on YouTube.

- Read on our blog for updates.

__________________________________________________

SFCG Lebanon team believes that entertaining tools are the best way to engage youth for peace. They have implementing projects with youth in Lebanon since 2008 already producing two TV series to spread messages of tolerance and acceptance of “the other” while promoting a united Lebanese identity beyond sectarian lines.